In the 1800s and 1900s, the brick-making process in the Hudson Valley was heavily influenced by the region's natural resources and advancements in technology. This process evolved from manual methods to more mechanized approaches, reflecting the industrial growth of the period.

Here’s how brick-making typically occurred in the Hudson Valley during that era:

1. Clay Extraction

The Hudson Valley was rich in high-quality clay deposits left by ancient glacial activity. Workers manually dug the clay from pits or quarries located near the river. The proximity to the Hudson River allowed easy transportation of raw materials and finished products by boat. Clay extraction was labor-intensive, involving shovels, pickaxes, and wheelbarrows before mechanization introduced steam shovels and dredging equipment.

2. Clay Preparation

The raw clay needed to be prepared for molding. This involved breaking down large clumps and removing stones and impurities. In the early 1800s, this was done by hand or with simple wooden tools. By the late 1800s and into the 1900s, machinery such as pug mills (powered by horses, steam, or water) mixed the clay and water, creating a consistent, moldable mass.

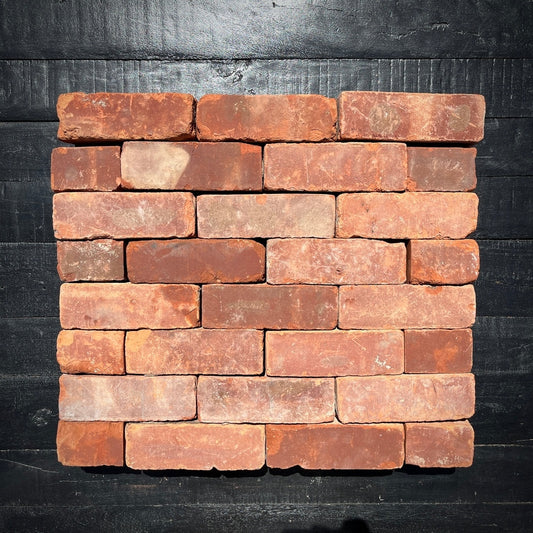

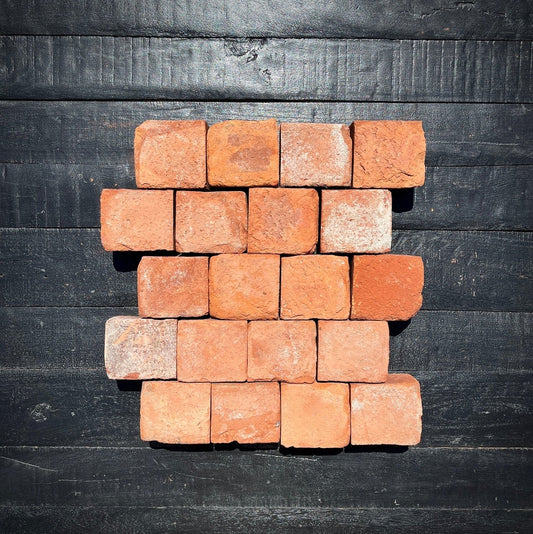

3. Molding

Initially, bricks were molded by hand, a process where workers pressed clay into wooden molds and scraped off the excess. Hand-molded bricks were not perfectly uniform but were adequate for building needs at the time. As demand increased, the late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the introduction of mechanical brick presses, which could mold bricks more efficiently and uniformly. These machines significantly sped up production and reduced the need for extensive manual labor.

4. Drying

The freshly molded bricks needed to dry before firing. In the 1800s, this was often done outdoors, where bricks were laid out in rows or stacked under shelters to dry naturally in the sun. This process could take days to weeks, depending on the weather. To speed up drying in wetter climates or seasons, brickyards sometimes used large drying sheds with heated air circulation by the early 1900s.

5. Firing

Once dried, bricks were stacked in large kilns for firing. In the early 1800s, traditional clamp kilns or scove kilns—simple structures made by stacking the bricks with fuel such as wood or coal in between—were common. As technology improved, more efficient *Hoffman kilns* were introduced in the late 19th century. These continuous kilns allowed for large-scale, consistent brick production by using a circular firing system with chambers that maintained a constant heat.

The firing process transformed the clay into a hard, durable brick. Kiln temperatures could reach around 1,800 to 2,000°F (about 1,000 to 1,100°C), which was hot enough to vitrify the clay and solidify the brick structure.

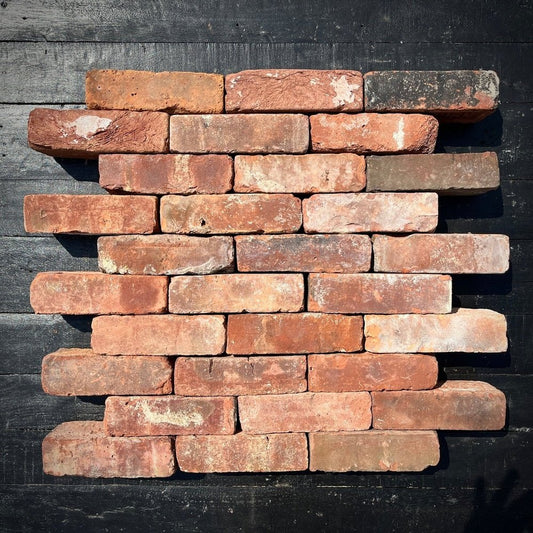

6. Cooling and Sorting

After firing, the bricks were allowed to cool before being removed from the kilns. Workers sorted the bricks by quality—some were perfect for construction, while others that showed cracks or deformities might be repurposed or discarded. The best-quality bricks were often used for facing work on buildings, while lower-quality ones might be used for internal construction or sold at a discount.

7. Transportation

One major advantage of the Hudson Valley brickyards was their proximity to the Hudson River. Finished bricks were loaded onto barges and transported downstream to New York City and other growing urban centers along the East Coast. This efficient steam-powered tugboats arrived in the 1880’s and greatly contributed to the profitability and growth of the brick industry in the region.

Tugboat Solicitor owned by Captain Charled Wieant of Haverstraw, Cornell Steamboat Co. Haverstraw Brick Museum Archives.

Challenges and Impact

The brick industry was labor-intensive, with many workers, including immigrants, employed in the brickyards. Despite the hard labor and seasonal nature of the work, brickyards provided significant employment. However, environmental challenges, such as the depletion of clay pits and the impact of excavation, were issues that communities would later address.

By the early to mid-20th century, the Hudson Valley brick industry began to decline due to the rise of alternative building materials (like concrete and steel), increased regulations, and economic shifts. The last major brickyards closed by the mid-1900s, marking the end of an era that had been vital to the development of the region and cities like New York.